El Massacre

-

0

-

0Shares

A story of deep wounds and of People without a Country

(in italiano piu' sotto)

A story by Edoardo Agresti

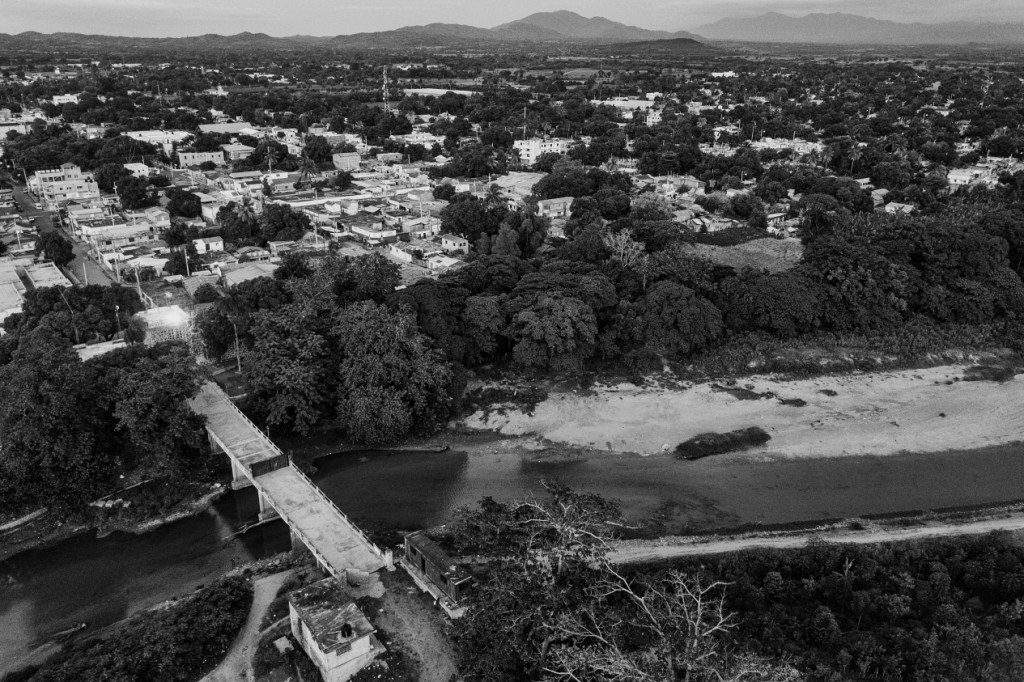

The Massacre River marks the border between Haiti (Ouanaminthe) and Dominican Republic (Dajabon) in the northwest of the island.

The Dominican Republic shares the Caribbean island of Hispaniola with Haiti, but the two neighboring countries might as well be across the globe from each other.

Dominicans are Latin and pride themselves on their Spanish roots, whereas Haitians speak Creole and are largely descendents of freed African slaves.

In the early 1900s, Haitians sugarcane cutters, lured by the promise of work, began the seasonal migration to the Dominican Republic—the Haitians were willing to do this low-wage, back-breaking work whereas most Dominicans were not. Over the decades, many of these sugarcane workers did not return to Haiti at the end of season, and thus created a large, permanent population of Haitians in the Dominican Republic—a population that was not welcomed.

The tensions between the two countries date back to many years ago culminating 80 years ago during the regime of Rafael Trujillo (1930–1961) that ordered an Haitian massacre - where more than 25,000 Haitians found outside the sugar plantations were killed) known as 'The massacre of parsley'.

The tensions between the two countries date back to many years ago culminating 80 years ago during the regime of Rafael Trujillo (1930–1961) that ordered an Haitian massacre - where more than 25,000 Haitians found outside the sugar plantations were killed) known as 'The massacre of parsley'.

The river - which is so called not for this episode, but for a bloody event that happened long before 1937 - was the place where thousands of Haitian bodies were found death. This deep wound has never been remedied and the relations between the two countries are continually very tense.

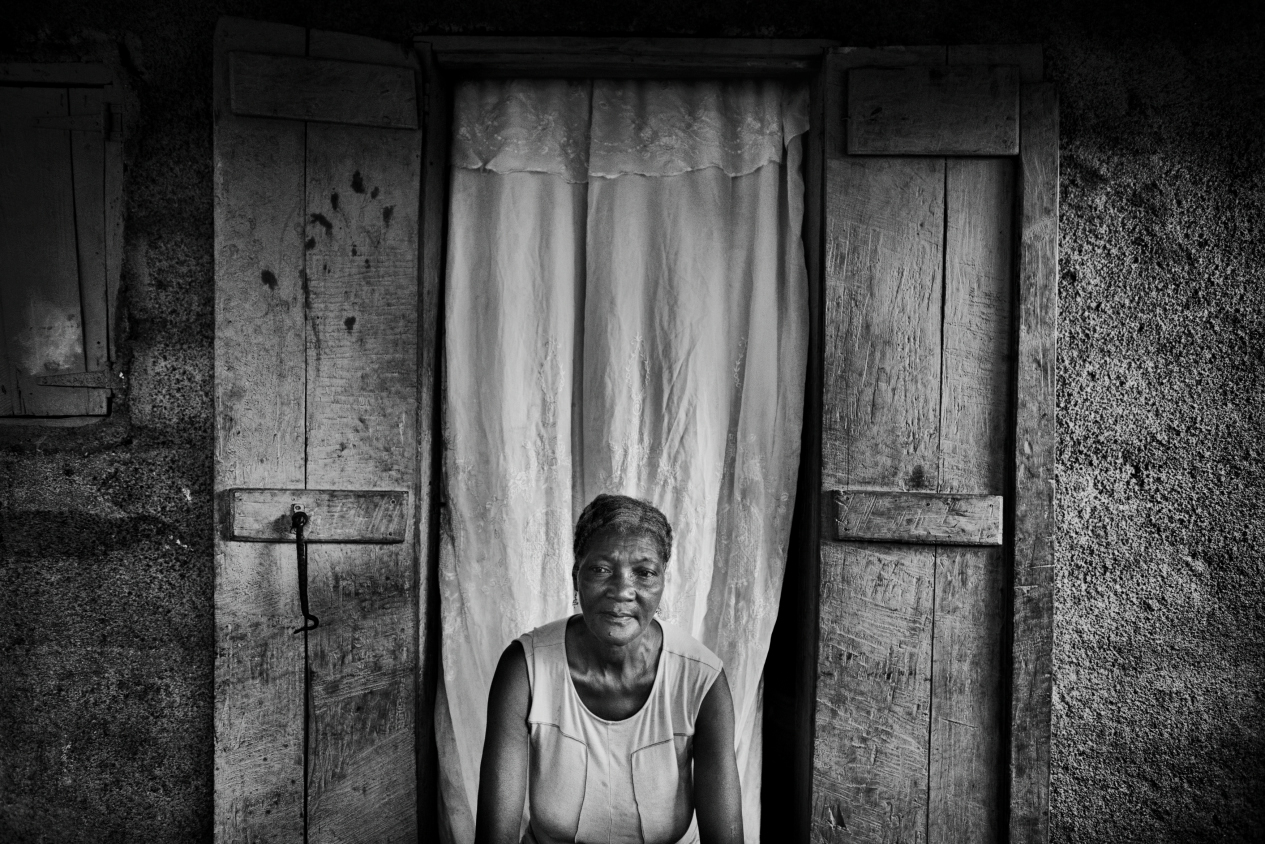

Throughout the late 1960s, ‘70s, and 80s, Haitian sugarcane cutters were confined to bateyes (company-owned towns consisting of nothing more than crude barracks surrounded by fencing) under the watchful eye of armed government soldiers. Their belongings were confiscated and they were trucked back and forth from the fields, often working from sun up to sun down. By the 1990s, the bateyes had become permanent home to hundreds of thousands of men, women, and children - second and third generation - Haitians born in the Dominican Republic, but with no legal citizenship status to be there and with no ties to their “homeland” Haiti.

They basically became a people without a country. Today the bateys remain the home of about 500.000 haitian and they still live in the same bad condiction (most do not have latrines, elettricity, rare potable water, raw road to reach, no education and healthcare).

The international economic crisis of the last years and the shifting of the center of gravity in the cultivation of the sugarcane in South America also heavily bad affected to the economic situation of the Dominican Republic and severely aggravated relations between the two peoples.

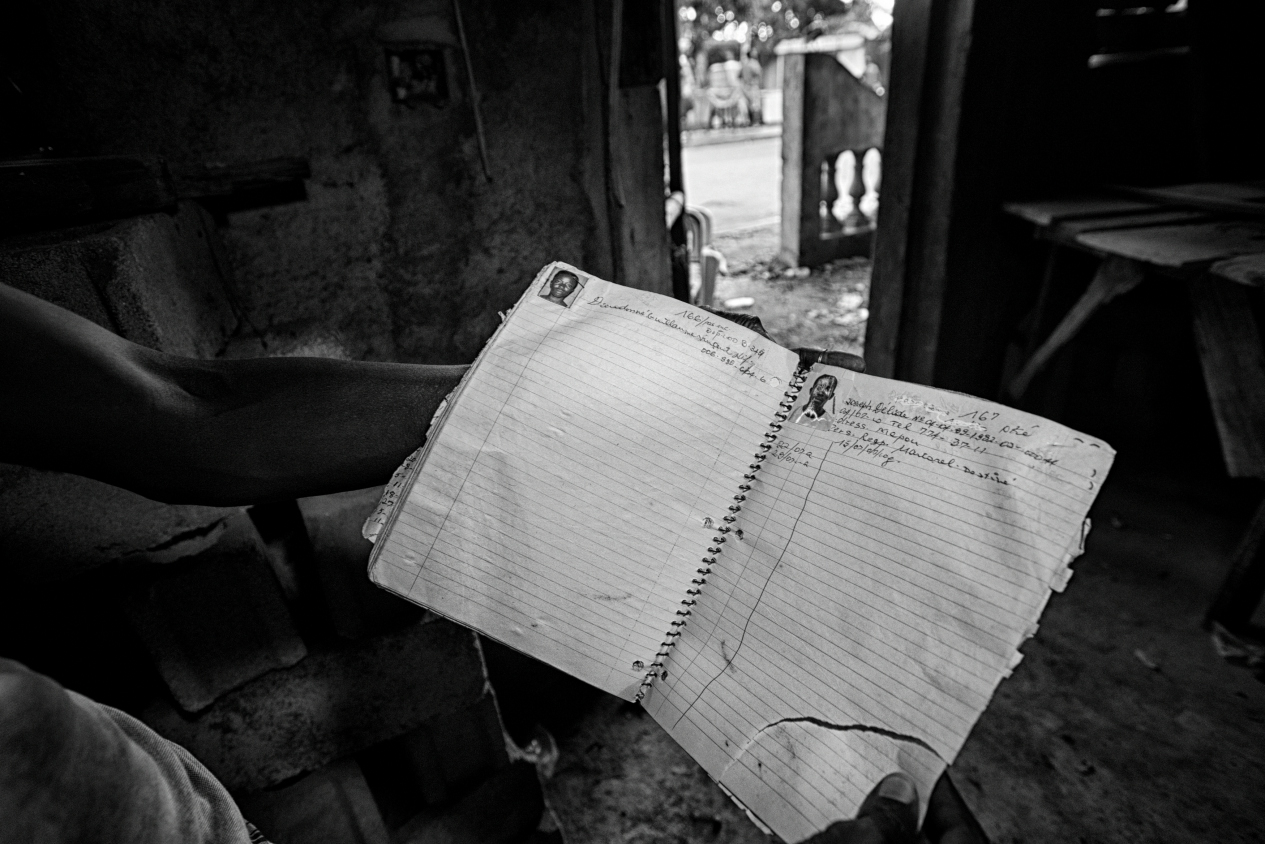

Dominicans have always been responsible for all their problems to Haitian immigrants. This attitude, which often resulted in real acts of racism, was exacerbated by a very absurd and controversial sentence, issued in September 2013 by the Dominican Government: the Constitutional Court abolished the ius soli as a valid criterion for the acquisition of citizenship and applied this new legislation retroactively starting from 1929. A measure capable of losing the nationality to over 200 thousand people, especially of Haitian origin, who from one day to another have precipitated into a state of statelessness, effectively losing any form of rights civil: from work to health, from medical assistance to education.

The harsh reaction of the international community, worried by this unprecedented and unanimously considered as a highly discriminatory legal scandal on a racist basis, has forced the Dominican government to activate a plan to regularize foreigners which, however, soon revealed itself to be a real charade. So, between June 2015 - after the deadline for submitting the application - and May 2016 over 100 thousand people would be repatriated to Haiti including threats, violence and mass deportations.

This law, also under pressure from the European Community, was frozen until the end of 2018 and so many Haitian immigrants continue to live in the bateys, even if without documents, in the terror that one day, at any moment, can arrive their turn to "return" to a land that mostly they have never known and of which they do not know even the language.

Edoardo Agresti/S4C

PHOTO GALLERY

La storia di una profonda ferita e di un popolo senza Paese

Testo e foto di Edoardo Agresti

Il fiume Massacre segna il confine tra Haiti (Ouanaminthe) e la Repubblica Dominicana (Dajabon) nel nord-ovest dell'isola, ma i due paesi pur condividendo l'isola sono profondamente divisi.

I Dominicani sono latini, parlano spagnolo e si vantano delle loro radici occidentali, mentre gli haitiani parlano il creolo e sono in gran parte discendenti degli schiavi africani.

Le tensioni tra i due paesi risalgono a molti anni fa e uno degli episodi più sanguinosi accaduti durante il regime di Rafael Trujillo (1930-1961) culminò, 80 anni fa, nell'ordine brutale di Trujillo di un massacro haitiano (dove più di 25.000 haitiani fuori dalle piantagioni di zucchero furono uccise) noto come "Il massacro del prezzemolo".

Il fiume - che è così chiamato non per questo episodio, ma per un evento sanguinoso accaduto molto prima del 1937 - è stato il luogo in cui migliaia di corpi haitiani sono stati trovati, uccisi mentre cercavano di fuggire e rientrare nel loro paese. Questa profonda ferita non è mai stata sanata e le relazioni tra i due paesi sono continuamente molto tese.

Agli inizi del 1900, i tagliatori di canna da zucchero haitiani, attirati dalla promessa di lavoro, iniziarono la migrazione stagionale nella Repubblica Dominicana, gli haitiani erano disposti a fare questo duro lavoro a basso salario e in condizioni di vita precarie, cosa che la maggior parte dei dominicani rifiutava.

Agli inizi del 1900, i tagliatori di canna da zucchero haitiani, attirati dalla promessa di lavoro, iniziarono la migrazione stagionale nella Repubblica Dominicana, gli haitiani erano disposti a fare questo duro lavoro a basso salario e in condizioni di vita precarie, cosa che la maggior parte dei dominicani rifiutava.

Nel corso dei decenni, molti di questi lavoratori non sono tornati ad Haiti alla fine della stagione della raccolta della canna, creando così una grande popolazione permanente di Haitiani nella Repubblica Dominicana. Una popolazione che, fin dagli inizi, non è stata accolta favorevolmente. Dalla metà degli anni '60 il Governo Dominicano costruì dei villaggi, poco più di baracche fatiscenti, intorno alle piantagioni di canna da zucchero. Durante la fine degli anni '60, '70 e '80, i tagliatori di canna da zucchero haitiani furono confinati in questi bateyes sotto l'occhio attento dei soldati del governo.

I loro beni furono confiscati e furono costretti a lavorare nei campi con turni massacranti, spesso lavorando dal sole fino al tramonto. Negli anni '90, i bateyes erano diventati la dimora di centinaia di migliaia di uomini, donne e bambini - haitiani di seconda e terza generazione nati nella Repubblica Dominicana, ma senza lo status di cittadinanza legale e senza legami con la terre di origine dei loro padri, Haiti.

Fondamentalmente sono diventati un popolo senza un paese. Oggi i bateys sono la casa di circa 500.000 haitiani e vivono ancora nella stessa cattiva situazione di quando furono eretti. La maggior parte non ha latrine, elettricità, acqua potabile, non ci sono scuole e assistenza sanitaria.

Haiti è sempre stata la parte povera dell'isola Hispaniola, spingendo molti giovani ad emigrare nella Repubblica Dominicana. La crisi economica internazionale degli ultimi anni e lo spostamento del centro di gravità nella coltivazione della canna nell'America del Sud hanno anche pesantemente influenzato il tessuto economico della Repubblica Dominicana e hanno fortemente aggravato i rapporti tra i due popoli.

I Dominicani hanno da sempre attribuito la responsabilità di tutti i loro mali agli immigrati haitiani. Questa atteggiamento, spesso sfociato in veri e propri atti di razzismo, si è acuito con una sentenza assai polemica e controversa, emessa nel settembre del 2013 dal Governo Dominicano: la Corte Costituzionale ha abolito lo ius soli come criterio valido all’acquisizione della cittadinanza e ha applicato tale nuova normativa in modo retroattivo a partire dal 1929.

Un provvedimento atto a far perdere la nazionalità a oltre 200mila persone, soprattutto di origine haitiana, che da un giorno all’altro sono precipitate in uno stato di apolidia perdendo di fatto qualsiasi forma di diritti civile: dal lavoro alla sanità, dall'assistenza medica alla scuola.

La dura reazione della comunità internazionale, preoccupata per tale scandalo giuridico privo di precedenti e unanimemente considerato come altamente discriminatorio su base razzista, ha costretto il governo dominicano ad attivare un piano di regolarizzazione degli stranieri che, tuttavia, si è presto rivelato una vera e propria messinscena. Così, tra il giugno del 2015 – scaduto il termine ultimo per presentare la domanda – e il maggio 2016, secondo i dati forniti da Amnesty International, oltre 100mila persone sarebbero state rimpatriate ad Haiti tra minacce, violenze e deportazioni di massa.

Questa legge, sotto anche le pressioni della Comunità Europea, è stata congelata fino alla fine del 2018 e così molti immigrati haitiani che continuano a vivere nei bateys, anche se privi dei documenti, nel terrore che un giorno, da un momento all’altro, possa arrivare il loro turno e siano costrette così a lasciare la Repubblica Dominicana per “tornare” in una terra che spesso non hanno mai conosciuto e della quale non conoscono neppure la lingua.

Edoardo Agresti/S4C

GALLERIA FOTOGRAFICA

-

0

-

0Shares

There are no comments

Add yours